The pages that follow will chart the development of motorway plans in London and the seemingly unstoppable rise of a network of roads called the Ringways. But they were only the last in a long line of attempts to solve London's traffic problems.

Before them came a succession of other ideas to help traffic move around the city more quickly: some more realistic than others, some more idealistic than others - and almost none ever reaching the point of being built.

In the beginning...

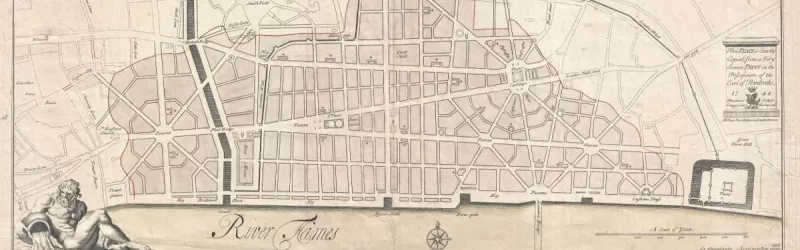

...was London, because London is a very old city. For as long as it has existed, traffic congestion has been an intractable problem. Every period in history has seen proposals to do something about it. The most famous might be Sir Christopher Wren's plan to rebuild after the Great Fire of 1666 on a new geometric grid of streets. Much to his disappointment, London returned to its old Medieval layout, traffic problems and all.

The first bypass of London was started in 1756 and was built so that drovers could avoid the city's narrow streets. The "New Road" is now known to us as Marylebone Road. At the time of its construction, it ran through countryside well outside the city, but that didn't last long.

London kept growing in its disorganised and haphazard way. It was only in the twentieth century that real improvements started to be made.

Making way for the motor car

Until the modern era, the traffic may have been bad, but all traffic was either horse-drawn or on foot. The population explosion in the nineteenth century was serviced by the railways and the Underground. But in the early twentieth century, motor cars started to appear on the streets, with the potential to go much faster, when traffic allowed. They were almost universally seen as a welcome development that cleared the streets of horses.

In 1903, a Royal Commission on London Traffic was established, and it reported in 1905. It demanded mass road widening and new bye-laws to control development and prevent obstructions to road plans.

The Commission's core proposal was for two major "avenues" that would quarter London's central area. An east-west avenue would link Bayswater with Whitechapel via the City, while a north-south route would link Holloway to Elephant and Castle. Both would carry trams and four-track underground railways would run beneath.

William Rees Jeffreys of the Road Improvement Association and the AA took a different view. He preferred ring roads, and submitted a proposal to the Royal Commission for a "boulevard round London".

Their encircling boulevards are the pride of many a continental city, and it is a crowning disgrace that, notwithstanding the absence of any great engineering difficulties, no road exists encircling the metropolis.

So far as possible, the new roads should consist of a number of separate tracks, viz., one for electric trams, a second for automobiles and cycles, a third for vans, carts, traction engines, and other slow-going traffic, and a fourth for foot passengers. They should be built throughout of dustless materials.

In the meantime, the Board of Trade and the Road Board set about doing what they could, and convened an Arterial Road Conference in 1910. Delegates from local authorities across London met and agreed on a programme of new roads, devising more than 100 miles of improvements. The First World War intervened before any progress was made.

In 1919, the Ministry of Transport was set up, and dusted off the Arterial Road proposals again. They created routes that remain some of the capital's busiest and most important even today, including the North Circular Road (A406), Eastern and Western Avenues (A12 and A40), the Southend Arterial Road (A127), the Barnet and Watford Bypasses (A1 and A41) and the Great Cambridge Road (A10). Most were complete by the mid-1930s.

London's new Arterial Roads transformed travel around the city and through its suburbs, but did little for the central area, and the success was short-lived as demand overwhelmed them. Few of the new roads were dual carriageway, and many were under 9m (30ft) wide. The traffic problem remained.

The need for improved communications

In 1934, the Ministry of Transport asked Sir Charles Bressey, an engineer, and Sir Edwin Lutyens, an architect, to "study and report on the need for improved communications by road...in the area of Greater London, and to prepare a Highway Development Plan". So they did, beginning with a survey of London's main roads, identifying 24 "centres of congestion". As if to underline how the Arterial Roads had failed to solve London's traffic problems, about a third of their trouble spots were on the brand new North Circular Road.

They recommended roundabouts at most of London's problem junctions, though the report included occasional urban cloverleaf interchanges and elevated roads, so bigger things may have been on their minds.

The main result of their work, published in 1936, were plans for 66 new roads. These did not follow a grid or any other overall pattern, instead running wherever traffic surveys suggested a need. Some were quite bizarre, travelling diagonally through the suburbs, while others were obvious, like a modern South Circular to match the new one in the north. An "East-West Connection", linking Western Avenue with Leytonstone, was included - a direct descendant of the Royal Commission's east-west avenue.

Perhaps Bressey and Lutyens' most visionary ideas were the North and South Orbital Roads. These were described as "parkways" up to 60m (200ft) wide, with flyovers at major junctions, orbiting London at a radius of about 32km (20 miles), comparable to the modern M25. Some of the North Orbital was built as the A405 and A414, and parts of it still bear that name on maps and street signs today.

The Highway Development Plan mostly recommended building ordinary roads, but Bressey did give a passing nod to the concept of motorways, which he suggested would be more appropriate for radial roads. He outlined five motorways beginning in the outer suburbs, travelling towards Birmingham, Nottingham, Basingstoke, Norwich and Brighton.

One thing all subsequent plans agreed upon was Bressey's argument that it was cheaper to build new roads than upgrade existing ones to a suitable standard.

The ten most badly needed new roads were selected by the Ministry in the hope they would be the start of a rolling programme, and the first five received Treasury funding in the late 1930s. Spades were about to hit the ground when war broke out in Europe once again, and all road construction was halted.

Wartime planning

The Second World War saw the destruction of homes and buildings across London, but there was considerable optimism for the building of a better city when hostilities ended. Lord Reith, better known as the BBC's first Director-General, was First Commissioner of Works during the War and oversaw bold plans for the reconstruction of Coventry, Plymouth and Portsmouth.

A masterplan was then commissioned to rebuild London after the war, correcting its "structural deficiencies": traffic congestion, poor housing, lack of open spaces and the mixing of homes and industry. Patrick Abercrombie, professor of Town Planning at University College London, was handed this mammoth task. He proved equally visionary in all four areas.

He produced two reports for the London County Council, full of the "brave new world" optimism that would permeate planning for the next few decades. The 1943 "County of London Plan" and the 1944 "Greater London Plan" looked, for the first time, beyond London's narrow administrative boundaries to "Metroland" and the leafy suburbs of the 1930s.

Abercrombie's plans were rigidly structured, organising the streets of future London into three categories. "Arterial Roads" were the most important, without frontages or access to side streets and with parallel service roads. "Sub-Arterial Roads" covered all other main roads, where frontage development would be permitted, service roads provided wherever possible and side streets blocked off. "Local Roads" covered everything else.

In the later 1944 report, he introduced a fourth category, "Express Arterial Roads", which had many of the characteristics of a motorway. They would be designed for motor traffic only, with a limited number of grade-separated junctions. Three possible junction layouts were suggested: a two-level roundabout interchange; a three-level roundabout interchange and a cloverleaf. Abercrombie carefully noted that he had modified the cloverleaf to turn its four loops into triangular roadways with sharp corners, though he didn't say why.

Eventually, Arterial Roads would carry through traffic, while local roads would be useful only for short journeys. Individual districts (or "precincts") would be self-contained to reduce the demand for travel. And for the first time, Abercrombie introduced structure to the road network: a system of concentric ring roads, with radial routes travelling out in all directions. This structure would be retained into the motorway age.

Abercrombie's new roads

The County of London Plan and the Greater London Plan called for five concentric ring roads identified by letters:

- The "A" Ring (Sub-Arterial), roughly where the Inner Ring Road and Congestion Charge boundary is today, forming "the boundary of the Empire, cultural and commercial core of London".

- The "B" Ring (Arterial), running a little further out and built for fast traffic. It was intended to be the main ring road and fully grade-separated like a motorway.

- The "C" Ring (Sub-Arterial), effectively the North and South Circular Roads. A bridge or tunnel would replace the Woolwich Ferry.

- The "D" Ring (Express Arterial) which would "girdle the general limits of the built-up area in London" as they then were.

- The "E" Ring (Sub Arterial), a revised version of Bressey's North and South Orbital Roads. It would have lay-bys and picnic areas, and would not join up across the Thames.

Main radial roads would be Express Arterial and interchange with the "B" Ring, and all radials were identified by numbers.

Two further roads would then cross the central area within the "B" Ring:

- Route "X", the old north-south avenue proposed by the Royal Commission, now an Arterial Road.

- Route "Y", the Royal Commission's east-west route, again as an Arterial Road.

When the War ended, Abercrombie's optimistic vision was held back by a crippling lack of funds. Responsibility for rebuilding London was split between various Ministries with little effective cooperation. And of course, thousands of people were homeless, or living in cramped and squalid conditions. The creation of vast new highways and rezoning projects couldn't be justified against the more pressing need to rebuild homes and commercial premises as quickly as possible.

By the 1950s, despite half a century of meticulous planning, post-war redevelopment had failed to provide any solution to the universally recognised traffic problem. Solving it would involve demolition, sometimes of buildings that had only recently been rebuilt. It was a whole new planning challenge.

Picture credits

- Christopher Wren's plan for London: public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Archive photograph of Great West Road under construction used under licence from London Metropolitan Archives, City of London (Collage record number 301310).

- Map of 1936 road plans is from the Highway Development Survey (1937), now out of copyright, and hosted by SABRE Maps.

- Plan of Bermondsey and sketch of "B" Ring flyover are from the County of London Plan (1943), JH Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie, published by Macmillan and now out of copyright.

Sources

- Christopher Wren's plan for London: Wren's Plans after the Fire (British Library); A Plan for Rebuilding the City of London (British Library).

- New Road, 1756: Pentonville Road (British History Online).

- Royal Commission investigation and report: The Royal Commission on the Means of Locomotion and Transport in London (1906).

- Arterial Road Conference and resulting construction: HLG 46/74; MT 39/23; MT 39/20; MT 39/511.

- Highway Development Plan: Highway Development Survey: General Report (1937), Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens, available at MT 39/360; roads approved by Treasury but halted by outbreak of war: MT 39/336.

- Commissioning Abercrombie's plans for London: London Road Plans 1900-1970 (1970), CM Buchanan, GLC Information Centre.

- Abercrombie's plans: County of London Plan (1943), JH Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie, Macmillan; Greater London Plan (1944), Patrick Abercrombie, HMSO.